Documenting a Musical Outsider

April, 15 2007

by: Christie Keith

Source: thebacklot.com

Edited by: Marcy

Official Website

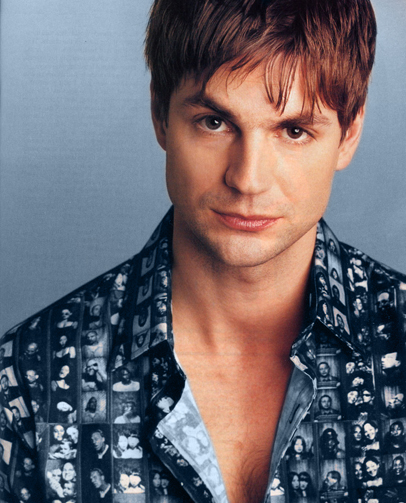

But that might be about to change — if queer filmmaker Stephen Kijak (Cinemania, Never Met Picasso) and actor Gale Harold (Queer as Folk) have anything to say about it.

I spoke with Kijak and Harold last month at the South by Southwest Film Festival in Austin, Texas, where their new documentary about the reclusive musical genius, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man, had its North American premiere. Harold was the film's associate producer and one of its earliest supporters.

You may never have heard of Scott Walker, but you've probably been under his spell — at least second-hand. After turning his back on U.K. pop stardom in the '60s when he split from his band, the Walker Brothers, at the height of their popularity, he started a solo career that moved ever deeper into experimentation and obscurity. Along the way, he brought the work of Belgian singer-songwriter Jacques Brel into vogue and influenced artists including David Bowie (who executive produced the film), Brian Eno, Alison Goldfrapp, Sting, Dot Allison and a long list of other musical luminaries, most of whom couldn't agree fast enough to be interviewed for the documentary.

In a music-centric interview that lasted more than an hour, Kijak told AfterElton.com, "I read an article once that said Scott Walker is Judy Garland for the gays who grew up writing poetry and wearing black turtlenecks." He laughed, then went on more seriously: "Scott is the benchmark for living an alternative lifestyle. He is uncompromising against anyone telling him 'this is how it's supposed to be.' He has one vision of himself, and he's expressing it through music."

Walker's code isn't only for musicians, Kijak insists. "It holds for anybody, in any pursuit in life that you can in some way think of as creative — even the construction of your own identity."

Kijak and Harold, without whom Kijak says the film would never have been made, first met at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. The two men discovered they shared an appreciation of — some might call it an obsession with — Scott Walker, and Kijak told Harold he was hoping to make a film about the musician. "I was working at the time, so I had money," Harold told AfterElton.com. "I told Stephen that if he got to the point where he was serious about making the film, I was there."

The two men share more than an interest in Scott Walker and the ability to talk for an apparently unlimited time about music. In separate interviews, they frequently echoed each other's thoughts, particularly about the theme of alienation they perceive in Walker's work, and its relevance to queer culture. During an interview — mostly, like Kijak's, centered on music — in an Austin bar, Harold described artists and queers as sharing an outsider sensibility, which is why he isn't surprised that gay audiences and artists are drawn to Walker.

"There's a very strong feeling of alienation in a lot of Scott's work," he said. "For anyone growing up with a strong need to create, to express yourself artistically, you experience that same sense of being alienated. If you're a gay man but you don't fit into the Abercrombie and Fitch model, or if you're a straight man who doesn't fit in with the NASCAR model — and that will be the culmination of everything wrong with American culture, the day Abercrombie and Fitch sponsors a NASCAR team — you feel that sense of alienation, of being an outsider."

He continued: "That gap in our culture, the one that exists outside the mainstream — that's where you find artists, gay people, all the outsiders. 'Queer culture' is bigger than most people think."

Gay artists, he said, can find themselves dealing with a double dose of cultural alienation. He talked about his teenaged years, listening to the Smiths while lying on his bed and staring out the window. He compared the group's enigmatic lead singer and lyricist, Morrissey, to Walker, and said: "Think about how hard it is for anyone to pick up a guitar, to become any kind of an artist at all, to overcome the obstacles to expressing yourself in that way. But add to that being gay and having to write your songs with elaborate metaphors and layers of meaning, because you can't really say what you mean. That makes it much harder — and almost always much better."

Kijak hasn't found it easy, either. "I don't connect with the mainstreamed, A-list gay culture," he said, "but then there are a lot of 'queer queers' who are out of the mainstream. … I feel like the alternative I belong to isn't a sexuality thing; it's your artistic pursuit, your point of view, your political, social and cultural beliefs, that set you apart."

Is that queer culture? "Definitely," he answered. "Unless a better word comes along soon, that's the one. Absolutely. My whole world has been lived on a fringe of exploring the arts, really extreme music and culture. That's what turns me on. … I think that's why I admire Scott so much. He says he feels like he's floating outside of culture and roots."

Walker is intensely, painfully private about his personal life, and Kijak respected that privacy while making his documentary. The focus of 30 Century Man is on Walker's musical story, told in riveting interviews with giants of the music world, speaking of Walker and his influence with reverence. Not bad for a man almost universally thought to be basically out of his mind.

"He's very serious and dedicated to what he's doing, but he's not crazy," said Kijak, who had unprecedented access to Walker 's studio during the recording of his most recent album, The Drift (2006). "At one point when we were filming a conversation with him and his colleague David Sefton. David said, 'You know, Scott, most people expect you to be off twitching in a cave somewhere, and you're not. You're just a regular person who makes irregular records.'"

Audiences can judge for themselves, said Harold, who pointed out, "You only have to watch the movie to know that Walker isn't crazy."

There are plenty of people who will tell you that Scott Walker is crazy. "Pretentious" and "self-indulgent" are words that come up a lot, too. And for Americans unfamiliar with Walker , it might be hard to fully understand the context in which his music exists, or the extent to which he broke with the musical expectations of his era.

From producing swirling pop hits, including the Burt Bacharach-penned "Make it Easy on Yourself" and "The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore," to the stunningly experimental work he's released on his last two albums, Walker has taken listeners on a journey no one could have predicted and many fans couldn't understand.

30 Century Man takes you on that journey with a guidebook, and despite its iconoclastic subject, is itself an accessible and beautifully structured film. It has received wide critical acclaim and is wowing film festival audiences around the world. Regardless of the film's success, however, Scott Walker, the musician, will be a tough sell.

That's nothing new for Walker. The slick, cynical marketing of musical talent didn't begin or end with the Backstreet Boys any more than the commodification of gay identity begins or ends with Abercrombie and Fitch ads. Even more today than when he first turned his back on mainstream success, Walker 's refusal to be sold — or even be made salable — is extraordinary.

"That's what really inspires me about Scott," said Harold. "He made a decision not to be commodified. He had a true artistic vision, and he made the choice to pursue that. He walked away not once but twice from fame and commercial success to pursue his art and his truth, on his terms. To be the person that he is."

Kijak, whose next project is a horror movie about a haunted East Village bedroom, said much the same, but pointed out that art and truth don't pay the bills. "I've done two documentaries in a row that are really low budget, and I'm just a broken man," he said, laughing. "These films have destroyed me. So I figure, let me try to do something a little more mainstream. And I'm sure Scott would be totally ashamed of me. If I was following his example, I'd go off and do another weird documentary. But I'm not. I'm not that strong."

Kijak has found it particularly hard to find a market for his work in the gay community: "This is why sometimes I feel like, how do you sell yourself? How do you sell yourself to 'the gays' when you feel excluded from them in some ways?"

It's not that Kijak hasn't made a gay project. "My first film [the Outfest award-winning Never Met Picasso in 1996] was a forgotten movie," he said. "We tried to sell it to here! television, and the woman actually said to me, 'Well, it's really not gay enough for our network.' I said, 'Did you actually watch it? It probably couldn't be gayer.' You've got a lesbian, a freaky transsexual, Alexis Arquette, hello, who defies categorization. Alvin Epstein, legend of the theater. All the characters. Craig Hickman. It wasn't gay enough for gays; it was too gay for straights."

Given the obstacles Kijak faced, how did a relatively unknown, queer American filmmaker get access to one of the most reclusive figures in music? It wasn't easy, he said, acknowledging what he calls Walker's "Garboesque reputation," but it was, in fact, his very outsider status that gave him both an insight and an edge.

"I think what they liked was that it wasn't the establishment," he said. "It wasn't the BBC; it wasn't British; it was just someone coming and saying, 'Let's do the Scott Walker story without all the baggage of having known his fame in the '60s, the screaming girls and the Walker Brothers and all that.' So [ Walker ] says, 'This is great. A young American looking into this story with a different, fresh perspective.' That appealed to them. And he's a crazy film buff, and he loved my last film. I sent him Cinemania. And he somehow felt some complicity with these people and liked the compassionate approach we took to a view of people on the fringe, to real outsiders. I think he felt like one of them in a way."

Visit our Video Picks page for a clip of Scott Walker's work.

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man screens at Hot Docs: The Canadian International Documentary Festival in Toronto April 21–22 and the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City on May 2, 3, and 5. For more information, visit www.scottwalkerfilm.com

Edited by Marcy